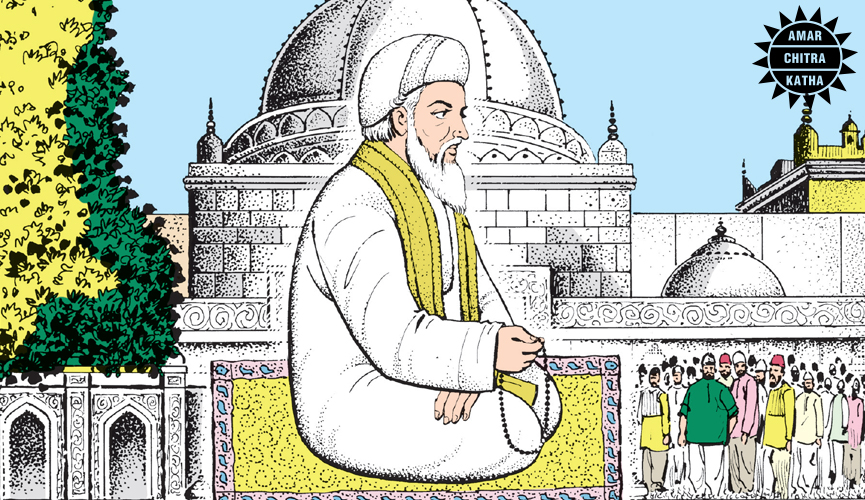

Jagat Guru of the Deccan – Ibrahim Adil Shah II

An Extract from the Forgotten Chronicles of Bijapur, 17th-century

Bijapur, 1620 AD – The court records, preserved in the fading ink of Deccani scribes, speak of a Sultan unlike any other. A king who bowed not only to Allah but also to Saraswati. A ruler who held the sitar in one hand and the Quran in the other. In a time of swords and conquest, he chose verses and ragas. This was Ibrahim Adil Shah II — the Jagat Guru of his age.

A Throne Among Thorns

Born in 1556 AD into the Adil Shahi dynasty, Ibrahim ascended the throne of Bijapur in 1580, a time when the Deccan was ablaze with ambition. The Mughal tide was surging from the north under Akbar, the Nizam Shahis of Ahmednagar and the Qutb Shahis of Golconda jostled for power, while the Vijayanagara remnants still held pockets of resistance in the south.

Yet, amidst this cacophony of war, Ibrahim turned Bijapur into something altogether different: a sanctuary of culture, music, and syncretic philosophy. While the world called him Sultan, his people began to whisper another name — Jagat Guru.

This wasn’t a mere title. It was a statement of his life’s work — to unify thought, art, and devotion across religions, languages, and castes. No other Deccan ruler would ever carry such a title again.

Kitab-e-Navras: The Soul of a Musician King

His greatest legacy remains not carved in stone, but penned in poetry — the Kitab-e-Navras, a literary and musical masterpiece that stands unmatched in Indo-Persian and Deccani heritage.

Written in Dakhani Urdu laced with Persian and Sanskrit, it was not a religious treatise, nor a court chronicle. It was something rarer — a manifesto of joy, love, and divine unity through the arts.

In one of its many verses, Ibrahim declares:

“Bhagwan is my witness, Rasool is my guide;

Music is my prayer, and every raga, divine.”

The Kitab-e-Navras (translated: Book of Nine Flavors) is structured around the navarasas, the classical Indian aesthetic emotions — shringara (love), karuna (compassion), veera (valor), and so on. Ibrahim explored these through lyrical compositions meant to be sung, not merely read. It was a living book, recited in court gatherings, danced in temple courtyards, and remembered long after his death by wandering minstrels of the Deccan.

Court of Many Faiths

What made Ibrahim’s reign exceptional was not only his cultural patronage but his fearless pluralism.

While his ancestors were Sunni Muslims and most of his contemporaries imposed orthodox structures, Ibrahim openly honored Hindu deities, especially Saraswati — goddess of learning and music — and Ganapati. He built temples within palace compounds, supported scholars from both Vedic and Sufi traditions, and commissioned translations of sacred texts across languages.

His court musicians played veenas and sarangis beside tamburas and rababs, while his poets — both Muslim and Hindu — composed in Persian, Sanskrit, Marathi, Kannada, and Dakhani Urdu. Among his closest courtiers were Hindu artists, Jain astrologers, Persian poets, and Sufi mystics — an unheard-of combination in any Deccan Sultanate of the time.

This wasn’t tolerance. It was devotional fusion.

Architecture of Sound and Stone

Under Ibrahim’s rule, Bijapur bloomed. While military campaigns were conducted by capable generals, the Sultan himself commissioned auditoriums, music halls, and gardens designed for acoustic resonance. Some structures had carved floral arches designed not just for light, but for echo — proof of a mind that saw architecture as part of music.

He expanded the Gol Gumbaz, one of the largest domed structures in the world, but also ensured that performances of ragas and devotional qawwalis echoed under the vaults of lesser-known shrines across his kingdom. Many of these buildings — now in ruins — carry inscriptions in both Persian and Sanskrit, some invoking the names of Allah and Shiva side by side.

A Gentle Dissenter in a Violent Age

While the great Mughals ruled with military might, and the Marathas were beginning their martial rise, Ibrahim carved a different niche: that of the philosopher-king.

He was no stranger to politics or war, yet he believed in outlasting his rivals not by steel, but by immortality through art. And in many ways, he did.

He chose to be remembered not as a conqueror of lands, but as a conqueror of the human soul.

The End and the Echo

Ibrahim Adil Shah II died in 1627, leaving behind not just a legacy, but a vision — one that saw India not as a land of divisions, but as a garden of blended faiths, tongues, and rhythms. His successors could not uphold the same harmony; the Adil Shahi dynasty eventually crumbled under Mughal pressure. But his memory survived.

Even in the 21st century, dusty libraries in Bijapur, Hyderabad, and Lucknow preserve aging manuscripts of Kitab-e-Navras. Musicians still attempt to revive his compositions. Cultural historians refer to him as the last true fusionist of India’s early modern era.

“He called Saraswati by name and offered her music from his soul. He bowed to Allah but kept the temple bells ringing. He ruled not with a sword, but with a raga. Such was the Sultan of Bijapur — Ibrahim, the Jagat Guru.”

Turning Deserts Green: The Story of One Man’s Mission to Reclaim the Land and Uplift Lives | Maya