Deadly Nerve Disease Surging in India — Linked to Water? A troubling outbreak of Guillain‑Barré Syndrome (GBS) in Maharashtra, India, has raised serious concerns about water quality, sanitation, and the role of bacterial and viral infections. Once considered rare, the condition is now appearing in clusters — especially in and around Pune. Here’s a detailed overview of the situation.

What is Guillain‑Barré Syndrome (GBS)?

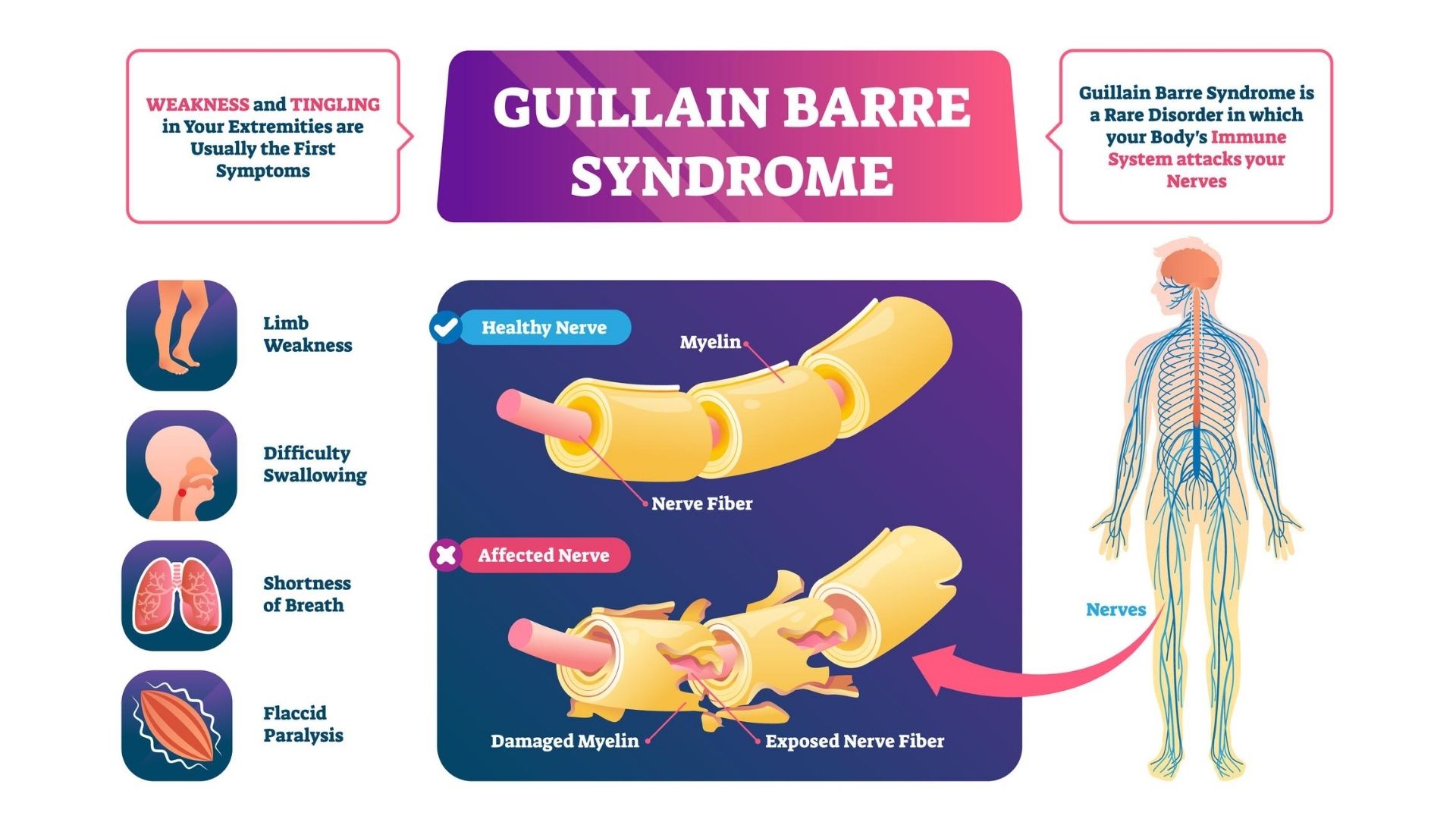

Guillain‑Barré Syndrome is an autoimmune neurological disorder where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the peripheral nerves. This often occurs after an infection, particularly involving the gastrointestinal or respiratory tract. Key symptoms include:

Tingling or numbness in limbs

Muscle weakness that can progress to paralysis

Loss of reflexes

Difficulty breathing in severe cases

GBS is a medical emergency. Though many people recover fully, the condition may require ventilator support and intensive care. Treatments like intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasmapheresis can improve outcomes if administered early.

The Outbreak: Numbers and Locations

Timeline & Spread

Period Location Reported Cases Key Areas Affected

Late 2024 – Early 2025 Pune region, Maharashtra Over 200 suspected and confirmed cases Villages newly merged into Pune Municipal Corporation: Khadakwasla, Nanded, Dhayari, Sinhagad Road, etc.

February 2025 Maharashtra (State-wide) Around 207 cases, 8 deaths reported Majority from Pune and surroundings

March 2025 Maharashtra 224 cases confirmed, 12 fatalities Clusters continue in Pune and nearby areas

The surge in cases has overwhelmed parts of the healthcare system, with several patients requiring ICU admission and ventilator support.

What Investigations Have Revealed

Infection Link

Laboratory testing in many affected individuals has confirmed:

Campylobacter jejuni — a bacteria linked to diarrheal illness — as a major pathogen.

Norovirus — a common stomach virus — detected in some cases, suggesting mixed infections.

These infections are known to precede GBS, especially Campylobacter, which has a well-documented association with nerve damage following gastroenteritis.

Water Contamination Suspected

Investigations found that many of the affected villages rely on poorly treated or untreated water sources. Water samples from these areas revealed:

Low or zero chlorine levels, indicating inadequate disinfection

Presence of coliform bacteria, Campylobacter, and viruses in drinking water

Contaminated private wells and tanker supplies, often outside municipal regulation

This points to unsafe drinking water as a likely trigger for gastrointestinal infections that then led to GBS.

Suspected Cause and Mechanism

The most likely chain of events in this outbreak:

1. People consumed contaminated water in newly merged suburban villages with underdeveloped water infrastructure.

2. They developed gastrointestinal infections, most commonly caused by Campylobacter jejuni.

3. In some cases, these infections triggered an autoimmune response, leading to GBS.

4. The sudden cluster of cases likely reflects both poor water sanitation and population exposure in high-risk areas.

What Remains Unclear

Despite strong evidence, some questions remain:

Not all cases had identified pathogens — more testing is needed.

The role of co-infections (e.g., both Campylobacter and Norovirus) is not fully understood.

It’s uncertain why only some infected people develop GBS — individual risk factors like genetics, immunity, or nutrition may play a role.

The extent of unreported cases in rural or under-resourced areas is unknown.

Government Response and Action

The outbreak has prompted a multi-tiered response:

Rapid response teams were sent to investigate and monitor new cases.

Water testing campaigns were launched across affected zones.

Some private water supply units were shut down for non-compliance.

The chlorination process in public water supply was reinforced.

Hospitals were equipped with ventilators, IVIG doses, and emergency beds.

Public health messaging urged people to boil drinking water and maintain hygiene, especially in outbreak zones.

Precautions for the Public

To reduce risk:

Boil or filter drinking water thoroughly.

Avoid using water from unverified sources (e.g., tankers, wells).

Watch for early signs of GBS — tingling, weakness, difficulty walking — and seek medical attention quickly.

Wash hands regularly, and avoid undercooked or unclean food.

In the long term, infrastructure improvements — especially clean water and sanitation in expanding urban zones — are essential.

Why This Matters

The current GBS outbreak is one of the largest recorded in India in recent years. It exposes serious vulnerabilities in basic public health systems — especially around water safety and infectious disease surveillance. While GBS is not contagious, the infections that trigger it are often preventable.

The cluster of cases centered around Pune serves as a warning for other cities experiencing rapid urban sprawl. Clean water, sanitation, and early medical intervention are critical — not just to treat GBS, but to prevent it from happening in the first place.