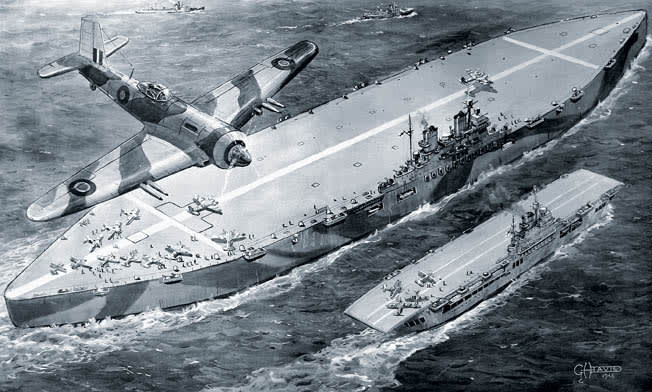

Could Ice Really Replace Steel in WWII? The Story of Project Habakkuk- When most people think of World War II engineering, images of tanks, battleships, and bombers come to mind—not massive aircraft carriers made out of ice. Yet during the early 1940s, British engineers seriously considered Project Habakkuk, an ambitious plan to build unsinkable aircraft carriers from ice and other frozen materials. It sounds like science fiction—but the idea was real, and it raises an intriguing question: could ice really replace steel in wartime?

The Origins of Project Habakkuk

Project Habakkuk emerged in 1942, when the Allies faced a major problem. German U-boats prowled the Atlantic, threatening supply convoys from North America to Britain. Traditional steel aircraft carriers were slow and costly to produce, and the Royal Navy needed a way to project air power into the mid-Atlantic, far from land-based airfields.

A British engineer named Geoffrey Pyke proposed a radical solution: construct enormous, unsinkable aircraft carriers from a new material called Pykrete, a mixture of ice and wood pulp. Pykrete was stronger and melted more slowly than pure ice. The concept was audacious: these massive ships could carry aircraft, survive torpedo attacks, and be built with abundant materials rather than scarce steel.

What Was Pykrete?

Pykrete is what made Project Habakkuk feasible—at least on paper. It’s composed of roughly 14% wood pulp and 86% water. The addition of pulp slows melting, increases toughness, and prevents ice from shattering. Scientists discovered that a block of Pykrete could withstand bullets, saws, and even small explosives better than normal ice.

Pykrete also had practical advantages:

-

It floated naturally, like ordinary ice.

-

It could be repaired easily by freezing water into cracks.

-

It could be produced in countries without steel shortages, such as Canada.

In theory, Pykrete seemed perfect for an aircraft carrier that needed to be massive, buoyant, and resilient.

How Would an Ice Aircraft Carrier Work?

The proposed Habakkuk carrier would be enormous—over 2,000 feet long, longer than any ship at the time. It would feature:

-

Thick walls of Pykrete reinforced with steel frames.

-

Aircraft hangars on top, allowing planes to take off and land.

-

Cooling systems to keep the ice from melting, including refrigeration units powered by the ship’s engines.

The idea was that the massive size and low density of ice would make it practically unsinkable. Torpedoes or bombs might chip the surface, but the overall structure would remain afloat.

Could Ice Really Replace Steel?

In theory, Pykrete offered some impressive properties, but in practice, there were huge limitations:

-

Temperature Sensitivity

Even with refrigeration, maintaining a massive ice ship in the North Atlantic was a logistical nightmare. Any mechanical failure could lead to catastrophic melting. -

Construction Challenges

Building a ship from ice would require enormous molds, refrigeration infrastructure, and constant maintenance. Transporting and assembling the Pykrete would be slow and difficult. -

Vulnerability to Fire

Aircraft carriers carried fuel and munitions. While Pykrete is resistant to bullets and shrapnel, fire would still be a major concern, especially near wooden reinforcements. -

Speed and Maneuverability

A ship made of ice would be slower and less maneuverable than steel vessels. This would make it difficult to evade submarines or stormy seas.

In short, ice could technically float and support weight, but it could not fully replace steel for operational warships.

Why Project Habakkuk Never Happened

Despite promising tests, Project Habakkuk was eventually abandoned. Engineers built small Pykrete models to test durability, and the results were encouraging—but scaling up to a full-sized aircraft carrier was impractical.

By 1943, the Allies had:

-

Improved anti-submarine warfare technology.

-

Built more steel carriers and long-range aircraft.

-

Found other logistical solutions for mid-Atlantic air coverage.

These advances made the extraordinary effort of constructing an ice carrier unnecessary. Project Habakkuk remained one of the war’s most creative “what ifs,” a testament to human ingenuity under pressure.

The Legacy of Project Habakkuk

Though it never reached the water, Project Habakkuk left a lasting impression on engineering and science:

-

Pykrete demonstrated that composite materials could dramatically change material properties.

-

The project inspired other experiments in unconventional materials and structures.

-

It remains a fascinating example of out-of-the-box thinking in wartime innovation.

Historians often cite Habakkuk as proof that necessity can drive even the most unusual technological ideas. The project reminds us that during crises, engineers and scientists are willing to test the boundaries of physics, imagination, and practicality.

Could It Work Today?

Interestingly, some modern engineers have revisited Pykrete and ice structures for civilian purposes. Concepts for floating ice cities, disaster shelters, and even futuristic architecture have drawn inspiration from the material. While using ice to replace steel in combat is still impractical, the science behind Pykrete has real-world applications in material science, cold-region engineering, and emergency construction.

In Summary

Project Habakkuk was one of World War II’s most extraordinary proposals: a floating, unsinkable aircraft carrier made of ice. The idea was born from desperation, innovation, and a willingness to challenge conventional engineering wisdom. While it ultimately proved impractical, the project demonstrated how humans can imagine radical solutions to seemingly impossible problems.

Could ice really replace steel? Not entirely—but Pykrete showed that with clever thinking, even the most unlikely materials could perform beyond expectations. Project Habakkuk remains a fascinating footnote in history, a symbol of wartime creativity, and a reminder that sometimes, the wildest ideas are worth exploring—if only on paper.

You Think NATO Is a Team Effort? The U.S. Pays for Most of It | Maya