The Shocking Truth About Rosa Parks That History Books Won’t Tell You- What if everything you learned about Rosa Parks in school was incomplete? The woman dubbed “The Mother of Freedom” was far more than a tired department store worker who accidentally sparked a movement. She was a strategic activist, a trained organizer, and a revolutionary who dedicated over sixty years to fighting injustice. This is her real story.

From Tuskegee to Activism: The Making of a Revolutionary

Born Rosa Louise McCauley on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama, she entered a world where racial segregation was not just custom but law. Her father worked as a carpenter and stonemason, while her mother taught school. When her parents separated during her early childhood, Rosa relocated to Pine Level, Alabama, with her mother and younger brother.

Growing up in the Jim Crow South meant navigating daily humiliations and dangers. Parks attended the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, an institution that provided education to Black students when opportunities were scarce. She later enrolled at Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes but had to withdraw when her grandmother fell ill. Despite these obstacles, she persevered and eventually earned her high school diploma—a remarkable achievement at a time when fewer than seven percent of African Americans completed high school.

A Partnership Built on Justice: Meeting Raymond Parks

The Shocking Truth About Rosa Parks That History Books Won’t Tell You- In 1932, nineteen-year-old Rosa married Raymond Parks, a barber who would profoundly influence her path toward activism. Raymond was already deeply engaged in civil rights work, particularly advocating for the Scottsboro Boys—nine Black teenagers wrongly accused of assaulting two white women in 1931. His dedication to justice inspired Rosa, though he initially worried about the dangers she might face.

By 1943, Parks joined the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, where she served as secretary. This wasn’t a ceremonial role—she investigated cases involving racial and sexual violence, documented injustices, and worked tirelessly to register Black voters. In those days, registering to vote meant facing deliberately complex tests, poll taxes, and outright intimidation. Parks attempted to register three times between 1943 and 1945 before finally succeeding.

During the summer of 1955, Parks attended the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, where activists learned practical resistance strategies. She studied effective protest techniques, including how to organize picket lines and establish citizenship training programs. This training would prove instrumental in the months ahead.

December 1, 1955: The Day That Changed Everything

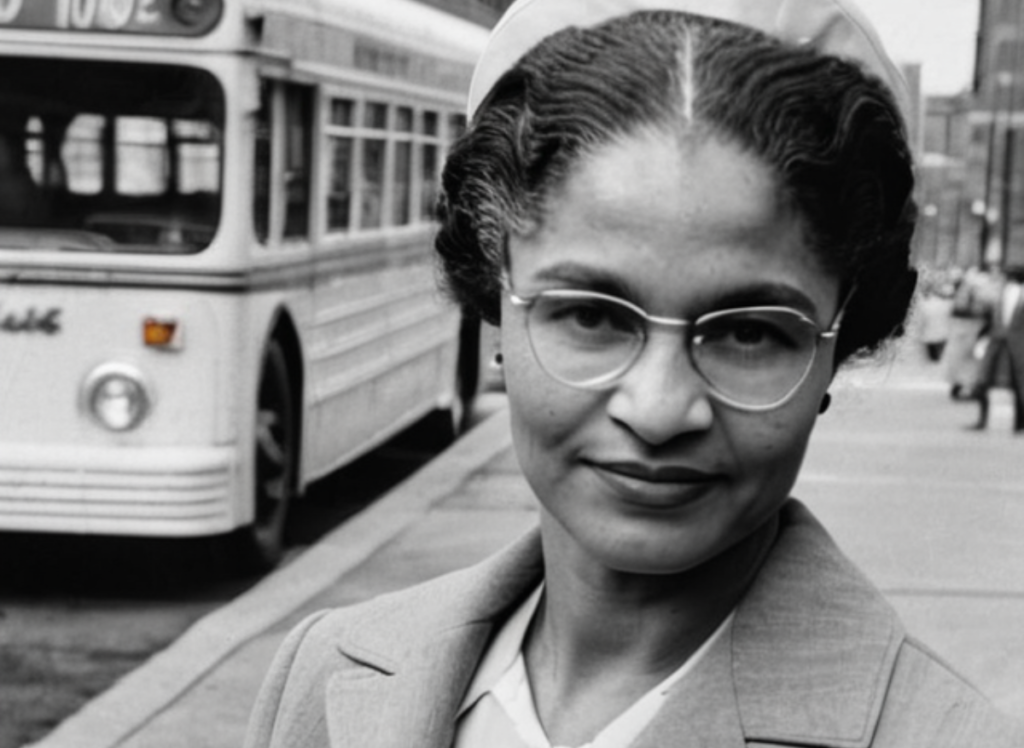

After finishing her shift as a seamstress at a Montgomery department store, Parks boarded a city bus on that fateful Thursday evening. She settled into a seat in the first row designated for Black passengers, directly behind the section reserved for whites. As the bus filled with passengers, driver James Blake demanded that Parks and three other Black riders surrender their seats to white passengers.

The other passengers complied. Parks did not.

Her refusal wasn’t born from physical exhaustion, as the myth often suggests. Parks later revealed that the brutal lynching of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till just months earlier—and the subsequent acquittal of his murderers—fueled her determination. She famously stated, “The only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Police arrested Parks and charged her with violating local segregation ordinances. She was convicted and fined ten dollars plus four dollars in court costs. But this wasn’t a spontaneous act by an ordinary citizen—it was a calculated stand by a seasoned activist who understood the power of civil disobedience.

381 Days That Shook America: The Montgomery Bus Boycott

News of Parks’s arrest spread rapidly through Montgomery’s Black community. Jo Ann Robinson, leader of the Women’s Political Council, along with E.D. Nixon, president of the local NAACP chapter, sprang into action. They printed and distributed thousands of leaflets calling for a one-day boycott of city buses on December 5th.

The boycott exceeded all expectations. Approximately ninety percent of Black residents—who comprised roughly three-quarters of bus ridership—stayed off the buses. Seeing this extraordinary unity, community leaders decided to continue the boycott until the city met their demands.

To coordinate the effort, activists formed the Montgomery Improvement Association and elected a young minister named Martin Luther King Jr. as its president. The MIA developed an elaborate carpool system involving approximately three hundred vehicles. When city officials attempted to shut down Black taxi services, volunteers stepped forward to drive their neighbors. Some walked as many as eight miles to work each day rather than submit to injustice.

The resistance faced brutal retaliation. In early 1956, bombs exploded at the homes of both King and Nixon. Protesters endured constant threats, harassment, and violence. Yet the community remained committed to nonviolent resistance, refusing to abandon their cause despite the dangers.

Victory in the Courts, Revolution in the Streets

On June 5, 1956, a federal district court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that Alabama’s bus segregation laws violated the Constitution. The city appealed, but in mid-November, the Supreme Court upheld the ruling. The federal order took effect on December 20, 1956.

After 381 days, the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended in triumph. The victory demonstrated that sustained, nonviolent mass protest could dismantle institutionalized racism. The boycott energized civil rights activism throughout the South and catapulted Martin Luther King Jr. into national prominence as a rising leader of the movement.

The Montgomery model would inspire future campaigns in Birmingham, Selma, and Memphis. King refined the philosophy of massive nonviolent civil disobedience—principles he studied from Gandhi’s work in India—and applied them to the American struggle for racial justice.

The Price of Courage: Personal Sacrifice

Victory came at tremendous personal cost. Parks lost her job as a seamstress when the department store fired her. Her husband Raymond was also terminated from his barbershop position after his employer prohibited him from discussing the case. The couple faced severe financial hardship and constant threats.

In 1957, seeking safety and opportunity, the Parks family relocated to Detroit, Michigan. Even there, they struggled economically, losing their apartment in 1959. Despite these challenges, Parks never retreated from the fight for justice.

Six Decades of Activism: A Lifetime of Service

Parks remained active in civil rights work for the rest of her life. She advocated for numerous causes and individuals, including supporting John Conyers, Joanne Little, Gary Tyler, Angela Davis, Joe Madison, and Nelson Mandela. She aligned herself with the Black Power movement and participated in anti-apartheid activism through the Free South Africa Movement.

In 1987, she and Raymond cofounded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development, an organization dedicated to providing career training for young people and teaching teenagers about civil rights history. Through this work, she ensured that future generations would understand the struggles and sacrifices that built the movement.

Reclaiming Her Story: Beyond the Myth

For decades, Parks was portrayed as an accidental heroine—a simple, tired woman who inadvertently sparked a movement. Recent scholarship has challenged this reductive narrative. Historian Jeanne Theoharis’s biography examines Parks’s six decades of activism, revealing a deliberate, strategic organizer rather than an accidental actor.

The Rosa Parks Papers, made available to the public at the Library of Congress in 2015, contain approximately 7,500 documents illuminating the breadth and depth of her lifelong commitment to justice. These materials reveal a complex, determined activist whose work extended far beyond that single act of defiance in 1955.

Recognition and Remembrance

Parks received more than forty-three honorary doctorate degrees throughout her life. In 1979, she was awarded the NAACP‘s Spingarn Medal. President Bill Clinton presented her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996, and in 1999, she received the Congressional Gold Medal. Time Magazine recognized her as one of the 100 most influential people of the twentieth century.

When Parks died on October 24, 2005, at age ninety-two, she became the first woman to lie in state at the United States Capitol rotunda. Public viewings were held in Montgomery, Washington D.C., and Detroit, allowing thousands to pay their respects to the woman who had changed America.

The Lasting Impact: Blueprint for Justice

The Montgomery Bus Boycott established principles that would guide civil rights activism for generations. It demonstrated the effectiveness of economic pressure, proved the power of nonviolent resistance, highlighted the necessity of organized leadership, and showed that legal challenges combined with mass action could achieve meaningful change.

The movement also revealed the critical role women played in organizing and sustaining civil rights campaigns. Beyond Parks and Robinson, countless women provided daily organizational support, participated in carpools, and maintained community solidarity throughout the boycott.

Montgomery became the model for subsequent campaigns throughout the South. The strategies developed during those 381 days would be refined and replicated in Birmingham, Selma, Memphis, and beyond, ultimately helping to dismantle legal segregation across America.

The Real Rosa Parks: A Legacy of Strategic Resistance

Rosa Parks was not a tired seamstress who stumbled into history. She was a trained activist, a strategic thinker, and a dedicated organizer who spent more than sixty years fighting for racial justice. Her refusal to surrender her bus seat was not spontaneous but deliberate—a calculated act of civil disobedience executed by someone who understood exactly what she was doing and why.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott did more than desegregate public transportation. It established the framework for nonviolent resistance that would define the civil rights movement and inspire freedom struggles worldwide. It proved that ordinary people, through extraordinary courage and collective action, could challenge and change unjust systems.

Parks’s legacy teaches us that social transformation requires both individual bravery and sustained collective effort. It reminds us that justice demands unwavering commitment over years and decades, not just moments. And it proves that when ordinary people refuse to accept injustice, they possess the power to reshape history.

The Mother of Freedom deserves to be remembered not as an accidental heroine but as the deliberate, courageous, brilliant strategist she truly was—a woman who changed America forever through six decades of fearless resistance to oppression.

How Do Multilingual Language Models Really Scale? DeepMind’s ATLAS Has an Answer | Maya