Fair Blame or Easy Target? The U.S. Role in Global Crises- In the discourse surrounding global conflicts, climate challenges, economic instability, and humanitarian disasters, the United States often finds itself at the center of blame. While some criticisms are valid, rooted in decades of foreign interventions and economic domination, others oversimplify complex global dynamics. Is the U.S. truly responsible for every major world crisis—or is it just the easiest target?

A History of Influence: Intervention and Consequence

The U.S. has long played a dominant role in international affairs, especially since World War II. Its military reach, economic power, and political influence shape global narratives. However, this influence has often come at a cost.

Consider the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Justified by claims of weapons of mass destruction—claims that later proved false—the U.S.-led war destabilized the region and left a power vacuum that contributed to the rise of extremist groups like ISIS. Similarly, American involvement in Afghanistan, Latin America, and Southeast Asia has often fueled unrest under the banner of promoting democracy or fighting communism.

These actions aren’t isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern of interventionism. In Latin America, the U.S. backed coups against democratically elected governments in Chile (1973) and Guatemala (1954), leading to decades of repression and conflict. In Vietnam, the war devastated not just Vietnam but also Laos and Cambodia.

It’s clear that U.S. foreign policy has sometimes prioritized strategic interests over stability or human rights, making it partially responsible for long-term consequences in these regions.

Economic Power: Helping or Hurting?

Beyond military intervention, the United States holds enormous sway over the global economy. Through institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank—both heavily influenced by U.S. policy—the U.S. has shaped economic reforms in developing nations for decades.

Often, financial aid comes with strings attached. Structural adjustment programs pushed by the IMF in the 1980s and 1990s required countries to cut public spending, remove subsidies, and open markets to foreign competition. While these policies aimed to stabilize economies, they also increased poverty, unemployment, and inequality in many regions, from Sub-Saharan Africa to Latin America.

However, it’s not all negative. U.S. foreign aid and investments have also improved infrastructure, healthcare, and education in various developing countries. But when these benefits are coupled with long-term dependency or financial debt, critics argue it creates a modern form of economic colonialism.

Reciprocal Tariffs and Economic Tensions

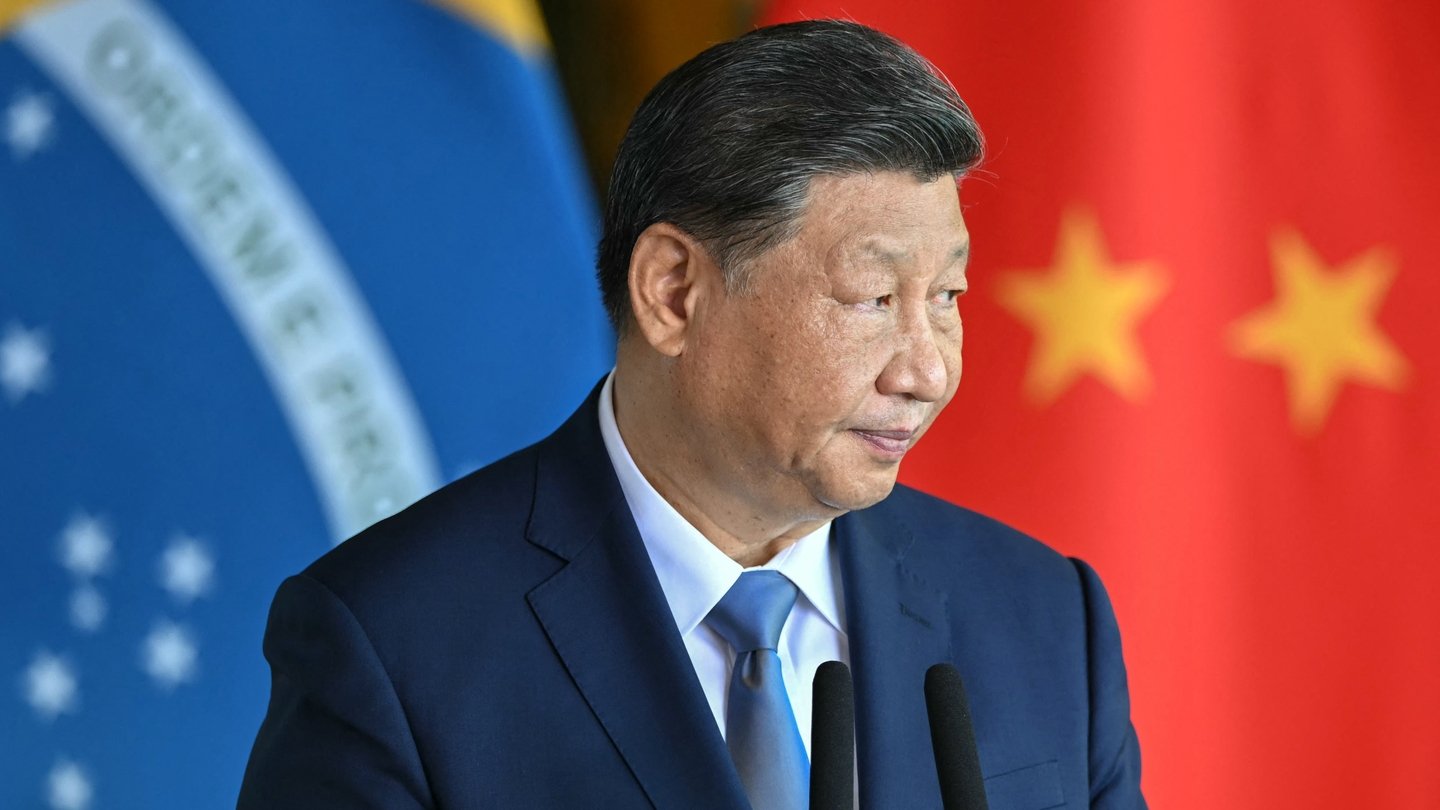

Trade wars, particularly under the Trump administration, added fuel to the global economic fire. The imposition of reciprocal tariffs between the U.S. and countries like China, the European Union, and even Canada disrupted global supply chains and raised prices on everyday goods.

These tariff battles were framed as a way to protect American industry and workers, but they also had global consequences. Developing nations that relied on exports suffered indirect effects due to reduced demand and higher trade barriers. The U.S.–China trade war, in particular, had ripple effects on Asian economies deeply integrated into China’s manufacturing base.

While tariffs may be a tool of negotiation, they are also a reminder that U.S. economic policies can reshape global markets—for better or worse.

Climate Change: Shared Crisis, Uneven Responsibility

No discussion of global crises is complete without addressing climate change. The U.S., as one of the largest historical emitters of greenhouse gases, bears significant responsibility. For decades, it delayed meaningful action, resisted binding international agreements, and prioritized industrial interests.

Though the U.S. has made strides in clean energy and rejoined the Paris Agreement under the Biden administration, critics argue that it still isn’t doing enough. Furthermore, the impacts of climate change disproportionately affect developing nations—those least responsible for emissions.

This brings us to a contentious issue: climate finance. Wealthy nations, including the U.S., have pledged billions to help developing countries adapt to climate change. But where is this money coming from?

Mostly from taxpayer funds in rich countries, though not nearly at the levels promised. Many Americans (and others in the West) question why their taxes should go toward repairing damage they didn’t directly cause, especially when domestic issues like healthcare, homelessness, and education remain underfunded.

How Long Must Rich Countries Pay?

There is growing fatigue in wealthier nations over foreign aid and global responsibility. Critics ask: how long must rich countries continue to pay for the failures or struggles of underdeveloped nations?

It’s a fair question—but it overlooks the systemic inequalities built over centuries. Colonialism, exploitation, unfair trade systems, and environmental degradation all disproportionately enriched the Global North at the expense of the Global South.

In many cases, underdeveloped nations are still repaying debts incurred during corrupt regimes or during periods of Western-backed economic policies. Moreover, global wealth isn’t evenly distributed due to random chance—much of it is a result of historical extraction, not just hard work or innovation.

Still, solutions require shared responsibility. The real issue isn’t whether the U.S. or Europe should contribute—but how to do it effectively and sustainably, with respect for local agency and accountability.

Is the U.S. an Easy Scapegoat?

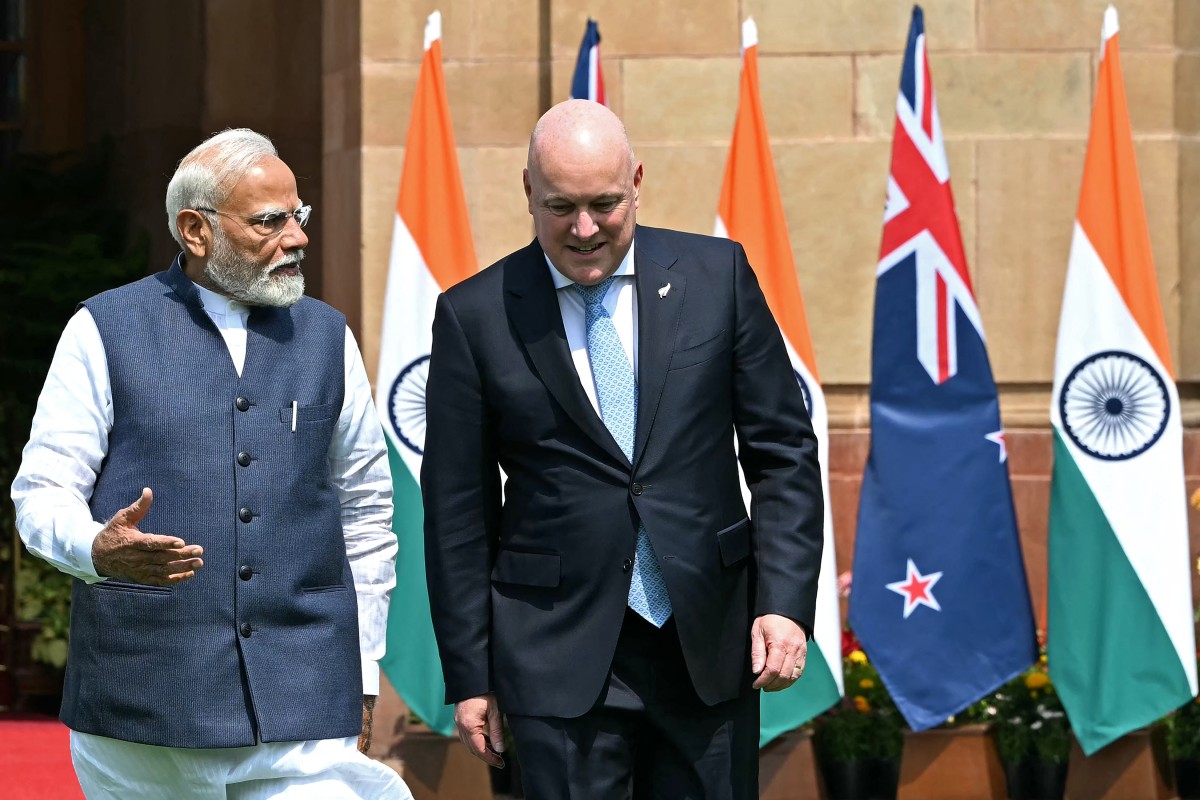

Given the U.S.’s global presence, it’s understandable that it often becomes the focus of blame. But the world is more multipolar than ever. China’s rising influence, Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, regional conflicts, and the role of multinational corporations all complicate the picture.

Blaming the U.S. for every problem ignores the responsibilities of local governments, other global powers, and internal dynamics within affected regions. For example, corruption, poor governance, and inter-ethnic conflicts often play a central role in ongoing crises—issues the U.S. did not create.

Moreover, nations like Russia and China have engaged in disinformation campaigns that amplify anti-U.S. sentiment, making it even harder to distinguish between valid criticism and propaganda.

Toward a Balanced View

So, is it fair to blame the U.S. for global crises? Sometimes, yes. But painting the U.S. as the sole villain oversimplifies complex global realities.

A more balanced approach is to hold all powerful actors accountable. That includes other nations, international institutions, corporations, and even the political classes within developing countries. Understanding this complexity is essential for crafting real, lasting solutions—not just pointing fingers.