How Did the Channel Tunnel Connect the UK and France? The Channel Tunnel, often referred to as the Eurotunnel or Chunnel, is one of the most significant feats of engineering in modern history. Spanning beneath the English Channel, it connects the United Kingdom to France, linking the two countries at their closest point. The tunnel has revolutionized transport, trade, and travel between the two nations, becoming a vital part of the European infrastructure. It has a profound geographical, economic, and cultural impact, shaping the way people and goods move across the English Channel.

Geographical Context

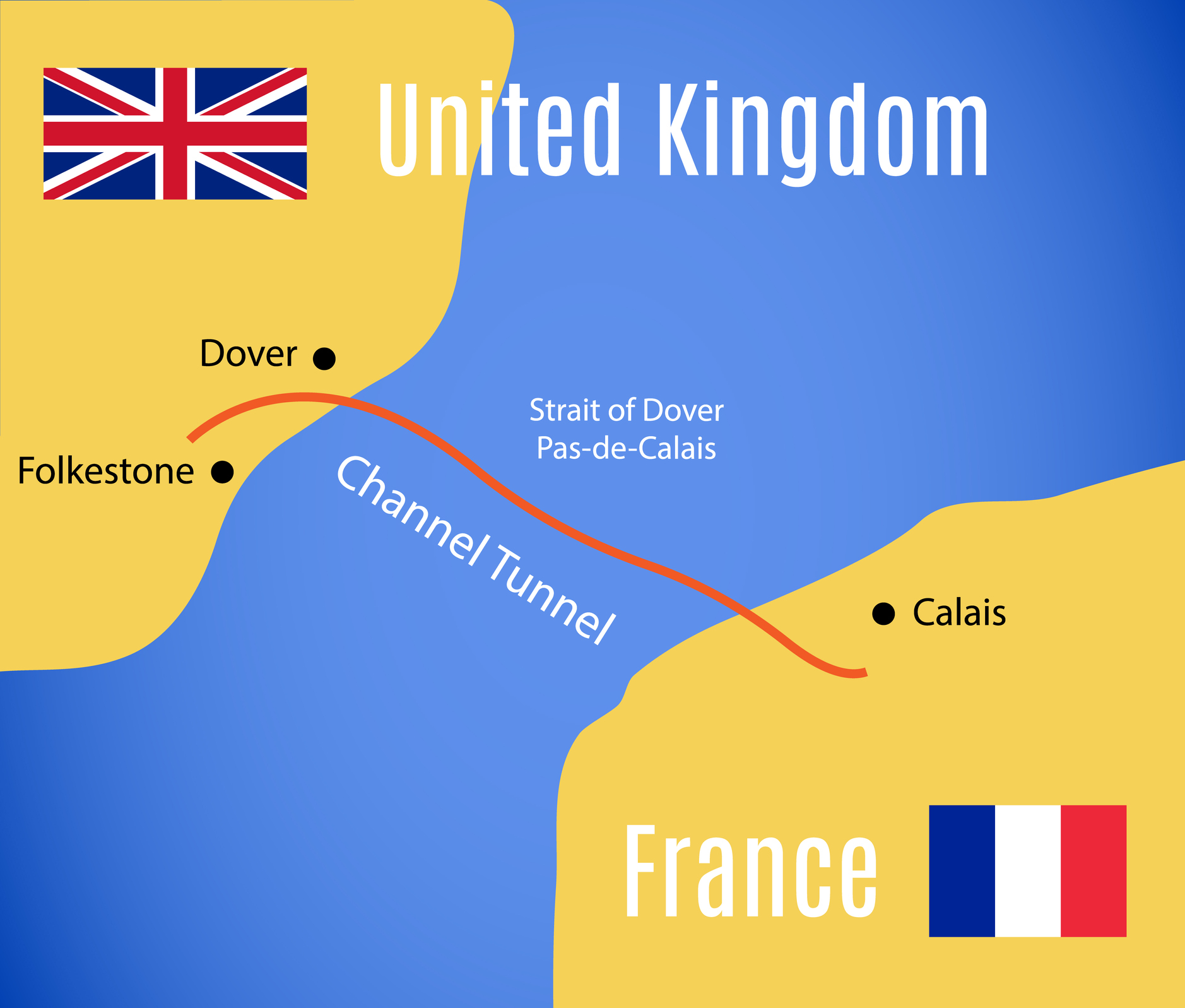

The English Channel, at its narrowest point between Dover in the UK and Calais in France, measures just 33.8 kilometers (21 miles). This relatively short distance had long made it an ideal location for a tunnel connecting the two nations. However, the idea of such a tunnel had been discussed for centuries, with many failed proposals dating back to the early 19th century.

The Channel Tunnel’s geographical significance lies in its strategic position as a major transportation link between the United Kingdom and mainland Europe. The Channel is a critical waterway, used by millions of people and goods annually, including ferries, container ships, and oil tankers. The region is also of great historical importance, having witnessed numerous military conflicts and maritime activities, including the famed D-Day landings during World War II.

Construction and Engineering Marvel

Construction of the Channel Tunnel began in 1988, following years of negotiations, planning, and technological innovation. The project was a joint effort between the UK and France, with the government-owned entities Eurotunnel in France and British Railways Board overseeing its development.

One of the biggest challenges was how to build a tunnel under the English Channel, where the seabed is covered by a mixture of clay and chalk. The project required cutting-edge tunneling techniques, including the use of Tunnel Boring Machines (TBMs), massive, rotating machines that could dig through the rock while keeping the tunnel structurally sound. These machines were deployed on both sides of the Channel—Folkestone in the UK and Coquelles in France.

Despite challenges such as the risk of flooding, geological issues, and logistical problems, the construction proceeded at a steady pace. The two tunnels met under the sea in 1990, marking a historic moment. By 1994, the tunnel was completed, with the final cost exceeding £9 billion.

The Channel Tunnel is comprised of three tunnels: two main rail tunnels, which accommodate high-speed trains for passengers and freight, and a smaller central tunnel used for maintenance and emergency access. It reaches a maximum depth of 75 meters (246 feet) below the seabed, with a total length of 50.5 kilometers (31.3 miles), making it the longest underwater tunnel in the world.

Transport and Travel

Today, the Channel Tunnel serves as a vital transportation route for both passengers and freight. The most well-known service operating through the tunnel is the Eurostar, a high-speed train service that connects London with Paris and Brussels. The journey takes just 35 minutes to travel between Folkestone and Coquelles, making it the fastest way to cross the Channel.

In addition to passenger services, the Channel Tunnel is a key route for freight transport. Trucks and vehicles can drive onto the Le Shuttle trains at terminals in Folkestone and Calais, where they are carried through the tunnel to their destination. This provides a significant advantage for the movement of goods, especially for businesses that need quick and reliable delivery across the Channel.

Economic Impact

The Channel Tunnel has had a profound economic impact on both the UK and France, fostering trade, tourism, and investment. Before the tunnel’s opening, the crossing of the Channel was limited to ferries or flights, both of which could be affected by weather or delays. The tunnel has provided a reliable and efficient alternative, streamlining cross-border travel and allowing for the faster movement of goods.

For businesses involved in logistics, the tunnel has been especially beneficial, reducing transit times and increasing trade efficiency. The Eurostar and Le Shuttle services have also boosted tourism, with millions of people now able to travel effortlessly between the UK and France.

Moreover, the tunnel has played a significant role in the integration of the European Union’s transport network, enabling smoother connections between the UK and mainland Europe. The Channel Tunnel has also promoted environmental sustainability by reducing the reliance on road and air travel, as rail transport is generally more energy-efficient and less polluting.

Challenges and Environmental Considerations

Despite its success, the Channel Tunnel faces various challenges. The operation of the tunnel involves high maintenance costs, and there are concerns about its capacity and the growing demand for cross-Channel travel. Furthermore, the tunnel’s location, under the English Channel, poses continuous challenges related to environmental protection and safety.

Geographically, the risk of flooding and the occurrence of seismic activity in the region have always been a concern. However, rigorous monitoring systems and engineering protocols have helped mitigate these risks, ensuring the safety of the tunnel and its users.

Final Thoughts

The Channel Tunnel is not just a transportation link between two nations; it represents a remarkable achievement in geography and engineering. It has connected the UK and France in a way that was once unimaginable, fostering economic ties, enabling cultural exchange, and facilitating tourism and trade. As one of the longest and deepest underwater tunnels in the world, the Channel Tunnel continues to stand as a symbol of human ingenuity and international collaboration. Its significance goes beyond its geographical position—it is a testament to what can be achieved when nations work together to overcome immense challenges.

Above the Earth: The Humility of Space’s First Pioneer | Maya