New Food Pyramid Ignites Debate Over Red Meat and Saturated Fat

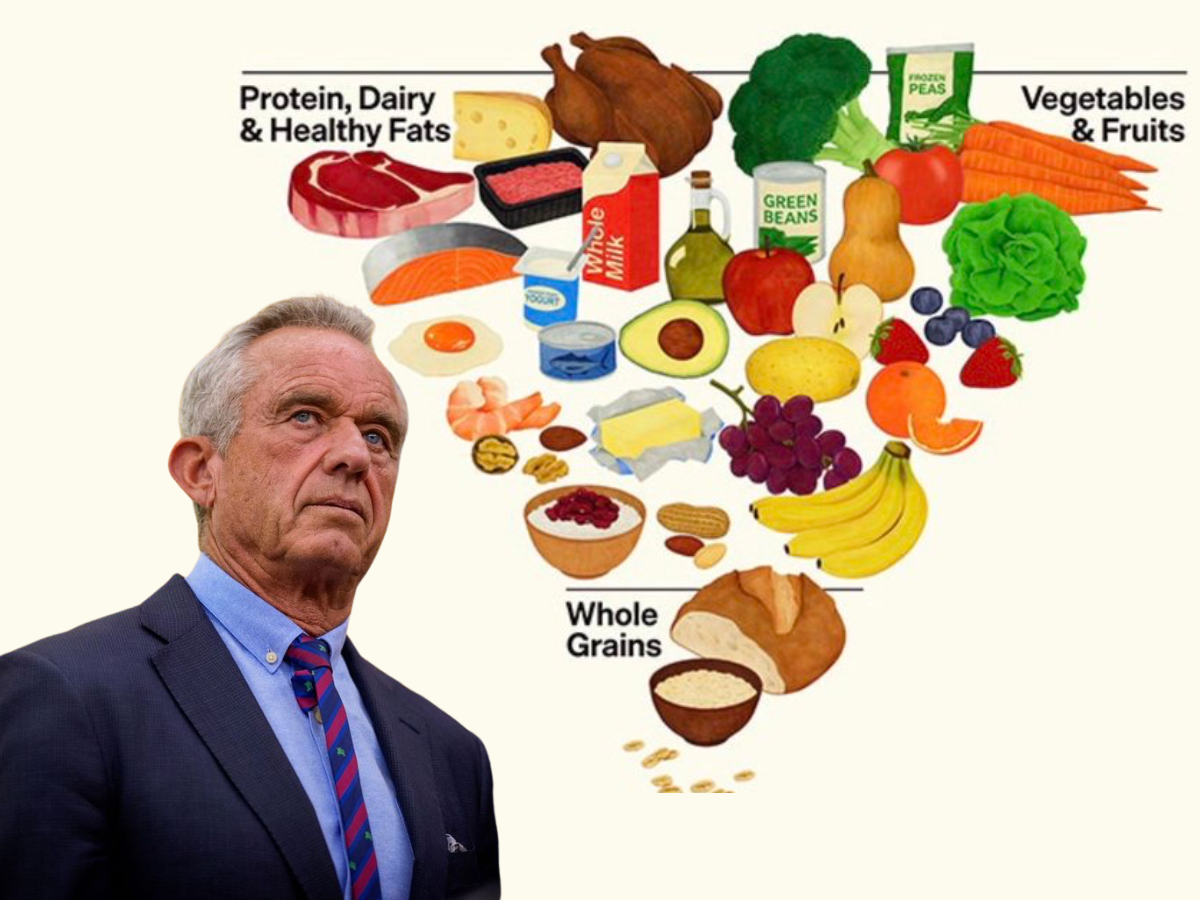

The federal government’s newly released food pyramid has reopened a long-running debate among nutrition scientists by placing red meat, cheese, fruits, and vegetables at the top of its recommended dietary framework.

Announced by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the updated guidelines mark a significant departure from decades of federal advice that urged Americans to limit saturated fat and prioritize low-fat foods. The administration says the shift reflects growing concern about the dominance of highly processed foods in the American diet and rising rates of chronic disease.

According to federal health data, more than 70% of U.S. adults are overweight or obese, and diet-related conditions such as heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, and hypertension remain leading causes of death. Officials argue that previous dietary guidance, which emphasized refined grains and low-fat products, coincided with an increase in consumption of ultra-processed foods high in added sugars and refined carbohydrates.

The new guidelines emphasize whole foods, adequate protein intake, and naturally occurring fats while calling for a sharp reduction in foods containing added sugars, excess sodium, industrial seed oils, and chemical additives. The recommendations also advise eliminating added sugar entirely for children under age 10.

Kennedy described the changes as a “reset” of U.S. nutrition policy, stating that protein and fats were unfairly demonized in past guidance. “We are ending the war on saturated fats,” he said, while noting that the guidelines still recommend limiting saturated fat intake to no more than 10% of daily calories.

The elevation of red meat and full-fat dairy has drawn criticism from some nutrition experts. Organizations such as the American Heart Association have long maintained that high intake of saturated fat is associated with elevated LDL cholesterol and increased cardiovascular risk. Average saturated fat consumption in the U.S. currently exceeds recommended limits, particularly among adults who consume large amounts of processed and restaurant foods.

“This pyramid sends a confusing message,” said Christopher Gardner, a nutrition scientist at Stanford University. Gardner and other critics argue that plant-based protein sources—such as beans, lentils, nuts, and seeds—provide fiber and micronutrients while lowering heart disease risk.

Others say the science around fat has evolved. Large observational studies and meta-analyses over the past decade have shown neutral or even protective associations between dairy consumption and cardiovascular disease. Full-fat milk, yogurt, and cheese have been linked to lower rates of stroke and Type 2 diabetes in some populations, challenging the assumption that fat content alone determines health outcomes.

“What seems to matter more is food quality and processing, not just fat percentage,” said Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian of Tufts University, who supports the guidelines’ focus on reducing processed foods. Nearly 60% of calories in the average American diet now come from ultra-processed foods, according to national nutrition surveys.

While most Americans never read the dietary guidelines directly, their influence is widespread. The recommendations shape school lunches, military meals, food assistance programs, and nutrition labeling standards—meaning the revised pyramid could affect millions of meals served each day.

As the debate continues, experts on both sides agree on one point: reducing reliance on highly processed foods could have far-reaching benefits for public health. What remains contested is how prominently red meat and saturated fat should feature in the American diet.

Can This Alien-Looking Veggie Replace Your Favorite Snack? | Maya