Why Denali May Not Look the Same in 10 Years- Towering at 20,310 feet (6,190 meters) above sea level, Denali is not only the tallest mountain in North America but also one of the most awe-inspiring natural landmarks on Earth. Formerly known as Mount McKinley, Denali stands as a sentinel over the vast wilderness of Alaska’s interior, drawing climbers, scientists, and Indigenous reverence for centuries.

Over the past decade, Denali National Park has become ground zero for climate change impacts. Warming at nearly twice the global rate, the region is experiencing accelerated glacial retreat, permafrost thaw, and landslide activity along the park’s only 92-mile road. Scientific projections suggest that by 2060, average annual temperatures in the park could rise by 5.8 °F (about 3.2 °C)—pushing the mean above freezing and causing near-surface permafrost, which currently underlies much of the landscape, to disappear entirely.

But behind its glacial façade lies a complex story — of naming controversies, climate challenges, cultural identity, and a rapidly changing landscape.

A Mountain of Many Names

For thousands of years, Indigenous Alaskans — primarily the Koyukon Athabascans — have referred to this peak as “Denali,” meaning “The High One” or “The Great One.” This name reflects its spiritual and geographic significance to native communities who believe the mountain holds sacred power and deep connection to ancestral lands.

In 1896, a gold prospector named it Mount McKinley in support of President William McKinley, a politician from Ohio who never visited Alaska. The name became official in 1917, despite widespread resistance from native groups and Alaskans.

After decades of debate, the U.S. government restored the mountain’s original Indigenous name in 2015, officially recognizing it as Denali. The change was praised as a symbol of respect for native heritage, though some political disagreement remained, especially from McKinley’s home state.

Geographical and Geological Wonders

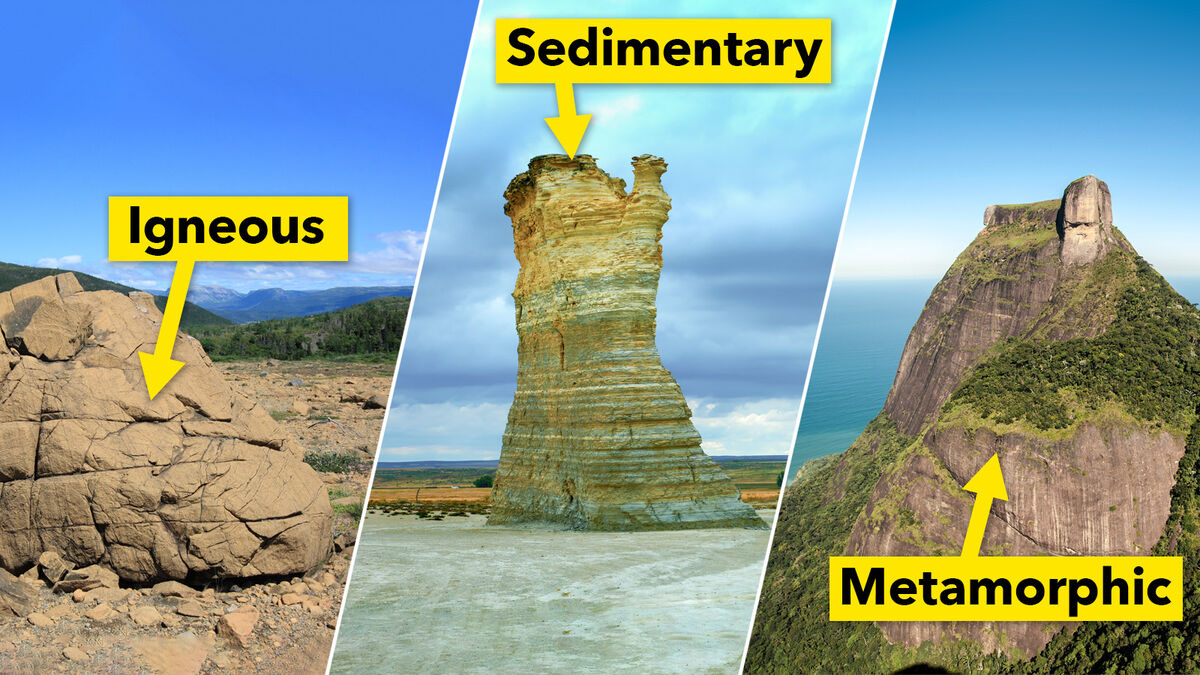

Denali rises from a base elevation of just 2,000 feet (610 m), giving it a vertical relief of over 18,000 feet — higher than Mount Everest when measured from base to summit. It is part of the Alaska Range, formed by the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the North American Plate.

The mountain is so large it creates its own weather systems, with temperatures dropping to -75°F (-59°C) and wind chills reaching -118°F (-83°C). Denali’s glaciers cover more than 45 square miles, and some of its icefields are thousands of years old.

Climbing Denali is a formidable challenge. Fewer than 50% of climbers reach the summit each year due to harsh weather and physical demands. It remains one of the coldest mountains ever climbed, and is often used by mountaineers training for Everest.

A Changing Climate at the Roof of North America

In recent decades, climate change has begun to reshape Denali’s ecosystem. Warming in Alaska is happening at more than twice the global average, and the region around Denali is no exception.

Recent studies from 2024 show that:

-

Glaciers are retreating at alarming rates, particularly the Kahiltna and Ruth Glaciers.

-

The snowline is rising, affecting seasonal water runoff and regional ecosystems.

-

Permafrost around the base is thawing, destabilizing soil and creating landslides.

-

Unusual weather events, such as mid-winter rainstorms, are becoming more frequent at high elevations.

Park rangers and scientists working in Denali National Park have observed increased rockfall, glacial melt, and changes in alpine vegetation. These changes threaten the delicate tundra ecosystem, wildlife migration, and even visitor safety.

Denali National Park: A Natural and Cultural Treasure

Denali National Park and Preserve, established in 1917, spans over 6 million acres — an area larger than the state of New Hampshire. It’s home to:

-

Grizzly bears, moose, wolves, and Dall sheep

-

Caribou herds and migratory birds like the golden eagle

-

One of the most accessible intact ecosystems in North America

Over 600,000 visitors come each year to witness Denali’s vast wilderness. The single park road, 92 miles long, is strictly regulated to protect wildlife and minimize human impact. Tourists can hike, camp, or explore the Polychrome Pass, Wonder Lake, and Teklanika River.

Cultural tourism is also rising, as Indigenous communities partner with the park to share their oral histories, traditional knowledge, and conservation practices rooted in deep ecological understanding.

Science, Conservation, and the Future

Denali serves as a climate research hotspot. Glaciologists, geologists, and meteorologists study the mountain to understand:

-

Long-term climate records from ice cores

-

The movement of tectonic plates

-

Alpine biodiversity and adaptation

The National Park Service, alongside organizations like the Denali Commission and local tribes, are working on adaptive strategies for:

-

Preserving native species

-

Monitoring glacial retreat

-

Managing visitor impact

-

Supporting sustainable development in nearby communities

In 2025, new remote sensing programs are being rolled out to track real-time changes in glacial mass and snowpack depth — vital data for both researchers and local ecosystems.

Why Denali Still Matters Today

Denali is more than a mountain. It’s a mirror of Earth’s natural power, a beacon of cultural pride, and a litmus test for climate resilience.

Its towering peaks remind us of:

-

The importance of honoring Indigenous names and histories

-

The fragility of remote ecosystems under climate stress

-

The need for balanced tourism and wilderness protection

As Denali continues to change, how we respond will determine whether future generations can still gaze upon its summit with the same sense of wonder and respect.